Abstract

Background and aims

The idea of treating COVID-19 with statins is biologically plausible, although it is still controversial. The systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to address the association between the use of statins and risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19.

Methods

Several electronic databases, including PubMed, SCOPUS, EuropePMC, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, with relevant keywords up to 11 November 2020, were used to perform a systematic literature search. This study included research papers containing samples of adult COVID-19 patients who had data on statin use and recorded mortality as their outcome of interest. Risk estimates of mortality in statin users versus non-statin users were pooled across studies using inverse-variance weighted DerSimonian-Laird random-effect models.

Results

Thirteen studies with a total of 52,122 patients were included in the final qualitative and quantitative analysis. Eight studies reported in-hospital use of statins; meanwhile, the remaining studies reported pre-admission use of statins. In-hospital use of statin was associated with a reduced risk of mortality (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.50–0.58, p < 0.00001; I2: 0%, p = 0.87), while pre-admission use of statin was not associated with mortality (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.79–1.77, p = 0.415; I2: 68.6%, p = 0.013). The funnel plot for the association between the use of statins and mortality were asymmetrical.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis showed that in-hospital use of statins was associated with a reduced risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many believe we are now approaching the end of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic by the ultimate discovery of effective SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. However, there is still a time gap before the global vaccination could finally be completed. In the meantime, we still need to take preventive measures for COVID-19 and its fatal complications by not only controlling specific chronic comorbidities [1,2,3,4], but also seeking the possible adjunctive treatment for patients already in severe COVID-19 condition [5].

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and thromboembolism are the two notorious complications that cause a high mortality rate among hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 [6, 7]. Current evidence suggests that lethal complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection originate from the “overactive” inflammatory response, which culminates in cytokine storms [8]. The initial inflammatory response occurs after the SARS-CoV-2 invasion cause disruption of both the epithelial and endothelial cells in alveoli [9, 10]. The subsequent endothelial dysfunction, release of inflammatory cytokines, thrombin generation, and fibrin clot deposition ultimately conclude in ARDS and catastrophic hypercoagulable state in COVID-19 [11].

Statins appear to hold the rationale as adjunctive therapy of COVID-19. Statins are more than lipid-lowering agents; they wield a pleiotropic effect with anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and antithrombotic properties [12,13,14]. Studies have shown that statins could improve the outcomes of patients with community-acquired pneumonia [15, 16]. However, the use of statins in COVID-19 patients is still controversial. Cariou et al. reported an increased risk of mortality among statin users [17], while Zhang et al. reported otherwise [18]. Therefore, we aimed to address the association between the use of statins and risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19.

Materials and methods

Data sources

Several electronic databases, including PubMed, SCOPUS, EuropePMC, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, with relevant keywords (“COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2”) AND (“statin” or “HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors” or “simvastatin” or “atorvastatin” or “rosuvastatin” or “pitavastatin” or “lovastatin” or “fluvastatin”) AND “mortality”, were used to perform a systematic literature search by three independent authors (HP, IH, and NS). We restricted the time of published articles from 1 December 2019 until our search finalization, which was 11 November 2020. Any duplicate records were removed after obtaining the initial results. By screening the title and abstracts, potential articles were then sorted. Afterwards, the full texts of the remaining articles were assessed for relevance based on eligibility criteria. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines was carried out as the core protocol in this study.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) research articles (either observational or interventional studies), (2) in adults patients with confirmed COVID-19 based on reverse transcriptase—polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test, (3) which had data on the use of statins (either pre-admission or in-hospital use of statins), and (4) reported all types of mortality. In-hospital use of statins was defined as the use of statins during hospitalization. In contrast, statins that were chronically or routinely taken before hospital admission were defined as pre-admission use of statins. The latter also included the use of statins, which was not explicitly stated as being continued during hospitalization. The outcome of interest was all types of mortality, including in-hospital mortality and 14- or 28-days (30-days) mortality. Non-research letters, review articles, case reports, research samples < 18 years old, and non-English language articles, were excluded from this study.

Data collection and extraction

Information from the included studies was collected by three independent authors (HP, IH, NS) using a pre-specified form. This form consisted of the first author, design of the study, location, samples, age, sex, use of statins (pre-admission or in-hospital), type and dose of statins, mortality, adjusted estimate, and covariates adjustment.

Study quality assessments

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), which is quality assessment tool for non-randomized studies [19], was used independently by the three authors (HP, IH, and NS) for the included studies. Any disagreements were decided through discussion.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis of included studies was conducted using STATA 16 (StataCorp LLC, Texas, US). In this analysis, hazard ratio (HR), odds ratio (OR), and risk ratio were regarded as comparable measures of risk estimates and defined as relative risk (RR) in this study. RRs of mortality in statin users versus non-statin users were pooled across studies using inverse-variance weighted DerSimonian-Laird random-effect models. Statistically significant values were considered if the P-values were < 0.05. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using I-square (I2) statistic, with a value of > 50 percent or P-values < 0.10 suggesting heterogeneity. Any significant heterogeneity was further assessed with leave-one-out sensitivity analysis. Funnel-plot asymmetry test was used to assess the presence of publication bias.

Results

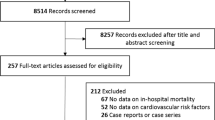

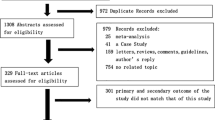

There were 812 records from our initial searches, which was reduced to 793 after duplicates removal. We excluded 762 records after title and abstract screening. After assessing 31 full texts of the remaining articles for eligibility, eight articles were excluded, because they did not report either number of mortality or adjusted estimates of mortality in the statin group. Five studies were also excluded because they did not report mortality as outcome of interest. Three other articles did not report the use of statin, while two articles were preprints. Thereby, 13 studies with a total of 52,122 patients met our inclusion criteria and were included in the final qualitative and quantitative analysis (Fig. 1) [17, 18, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Eight studies reported in-hospital use of statins; meanwhile, the remaining studies reported pre-admission use of statins. The baseline characteristics of the included studies can be seen in Table 1.

In-hospital use of statins and mortality

In-hospital use of statin was associated with a reduced risk of mortality (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.50–0.58], p < 0.00001; I2: 0%, p = 0.87) (Fig. 2).

Pre-admission use of statins and mortality

Pre-admission use of statin was not associated with mortality (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.79–1.77], p = 0.415; I2: 68.6%, p = 0.013) (Fig. 3). Leave-one out sensitivity analysis could not significantly reduce heterogeneity.

Quality assessment and risk of bias

Most studies included in this analysis were considered as high quality (Table 1). The risk of bias was mainly due to insufficient data validators and inadequate data reporting. The funnel plot for the association between the use of statins, both in-hospitals and pre-admission, and mortality were asymmetrical (Fig. 4a, b).

Discussion

The differentiation between in-hospital and pre-admission statins use proved to be the key explanation that illuminates the conflicting evidence of previous studies. The association between statins and increased risk of mortality among hospitalized diabetic patients with COVID-19 was previously reported by Cariou et al. [17]; however, the authors explicitly stated that they lacked information on whether statins were continued during hospitalization. Suppose the study sample on diabetic patients was used as a justification for this occurrence. In that case, it could not explain the results of Saeed et al., which showed a significant reduction of in-hospital mortality among diabetic patients with COVID-19 receiving statins [21].

This current meta-analysis showed that in-hospital use of statins was significantly associated with reduced risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19. The mortality risk reduction was almost 50% compared to non-statin users with good consistency across all the included studies. Meanwhile, pre-admission use of statins did not exert the same benefit. Previous two meta-analyses in smaller scales showed conflicting results. Kow et al. reported that the use of statins significantly reduced risk for fatal or severe disease in COVID-19 [31], whereas Hariyanto et al. showed the insignificant associations between statins and poor outcome [32]. Interestingly, both of the studies did not differentiate between in-hospital and pre-admission use of statins. This differentiation further translated into low levels of heterogeneity and statistically significant association.

Statins are widely known as lipid-lowering agents with pleiotropic effects on inflammation, immunomodulation, and oxidative stress [13]. Despite their pharmacodynamic properties, statins are readily available, inexpensive, and have well-established safety profiles, which contribute to the ongoing use of these drugs to improve disease outcome in influenza and other viral illnesses [33]. The use of statins in reducing mortality among hospitalized patients infected with influenza was reported previously by Vandermeer et al. and Laidler et al. [34, 35], although the latter concluded that the unmeasured variables may confound the effect. However, the evidence that statins reduce mortality in influenza patients has led to their consideration as potential adjunctive treatments to reduce mortality in emerging viral diseases likely to cause significant epidemics [36].

Numerous experts postulated that the benefits of statin in COVID-19 might be related to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expressions [13, 37]. ACE2 is the tissue receptor that facilitates the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells [38]. This receptor is expressed not only in the lungs but is also found throughout the body, including the heart, vasculature, brain, gastrointestinal tract, and the kidneys [39]. ACE2 plays an important role in counter-regulating the renin–angiotensin system, especially in the conversion of angiotensin (AT) II to AT-(1–7). AT-(1–7) counteracts the effects of AT II, which induces inflammation, increased oxidative stress, vasoconstriction, and fibrosis, leading to tissue injuries [40]. A previous study reported that statins increase the expression of ACE2 by approximately two-fold [41], and the increased activity of ACE2 has been associated with decreased incidence of ARDS [42]. Nevertheless, whether there is an association between ACE2 activities and the severity of COVID-19 is still a matter of debate. A recent trial of medication known to upregulate ACE2 expressions showed no effects on the outcome of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 [43, 44].

This study's novel finding, which was the mortality risk reduction only among hospitalized COVID-19 patients with in-hospital use of statins, might be due to the drug's direct antiviral effects (Table 2). Statins may prevent SARS-CoV-2 entry to the respiratory epithelial cells through the modulation of CD-147, a cell surface protein with an essential role in facilitating viral access to the host cells [45]. Furthermore, the drugs could inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication by directly interacting with the viral main protease (Mpro), which serves as a key enzyme in proteolytic maturation [46]. The direct nature of antiviral actions of statins in COVID-19 theoretically conveys its benefit only when the drugs are actively taken; thus, pre-admission use of statins could not wield the same effects.

Another potential biological hypothesis on the benefits of using statins to treat COVID-19 relates to their anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and antithrombotic properties [12]. Hyper-inflammatory condition leading to cytokine storms along with hypercoagulable state are considered hallmarks of severe COVID-19 [47]. These conditions may ultimately culminate in MOF and even death [48]. Statins may confer their benefit in attenuating inflammation by the modulation of Toll-like receptor and NOD-like receptor activities [49], thus reducing the hyper-inflammatory state in severe COVID-19. It has been shown previously that high dose administration of simvastatin can reduce the production of IL-6 and IL-1β cytokines [50]. The advent of lung pathology has facilitated the observation of occlusion and micro-thrombosis in the small pulmonary vessels of critically ill COVID-19 patients [51]. It has elucidated the benefit of using anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized COVID-19 patients [52]. It seems that the antithrombotic activities of statins could also play a role. The use of statins is associated with decreased plasma levels of von Willebrand factor antigen (vWF:Ag) and plasma endothelin-1 concentrations [53, 54]. Reduced concentrations of both plasma vWF:Ag and endothelin-1 contribute to the antithrombotic properties of statins.

Although this meta-analysis showed preliminary evidence for in-hospital use of statins in reducing the risk of mortality among patients with COVID-19, there were several possible caveats. Any verdict regarding the benefits of statins on the outcome of COVID-19 patients could not be drawn conclusively due to the nature of retrospective and observational studies included in this analysis. These included studies could not accurately measure the strength of the association; thus, further randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm the benefits of statins. Moreover, cautious interpretation of the findings of this meta-analysis should take into account the possible presence of publication bias as denoted by the asymmetrical funnel plot. Lastly, the type and the dose of statins in more than half of the included studies were mostly not described.

Conclusion

In-hospital use of statins was associated with a reduced risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19. Meanwhile, pre-admission use of statins did not exert the same effect.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.

References

Pranata R, Supriyadi R, Huang I, Permana H, Lim MA, Yonas E, et al. The association between chronic kidney disease and new onset renal replacement therapy on the outcome of COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2020;14:1179548420959165. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179548420959165.

Andhika R, Huang I, Wijaya I. The severity of COVID-19 in end-stage kidney disease patients on chronic dialysis. Ther Apher Dial. 2020;50(1744–9987):13597. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-9987.13597.

Wijaya I, Andhika R, Huang I. Hypercoagulable state in COVID-19 with diabetes mellitus and obesity: is therapeutic-dose or higher-dose anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis necessary? Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14:1241–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.07.015.

Yonas E, Alwi I, Pranata R, Huang I, Lim MA, Gutierrez EJ, et al. Effect of heart failure on the outcome of COVID-19—a meta analysis and systematic review. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;155:104743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.07.009.

Wijaya I, Andhika R, Huang I. The use of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation and its effect on mortality in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review. Clin Appl Thromb. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/1076029620960797.

Hasan SS, Capstick T, Ahmed R, Kow CS, Mazhar F, Merchant H, et al. Mortality in COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome and corticosteroids use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2020;14:1149–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2020.1804365.

Malas MB, Naazie IN, Elsayed N, Mathlouthi A, Marmor R, Clary B. Thromboembolism risk of COVID-19 is high and associated with a higher risk of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29–30:100639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100639.

Hojyo S, Uchida M, Tanaka K, Hasebe R, Tanaka Y, Murakami M, et al. How COVID-19 induces cytokine storm with high mortality. Inflamm Regen. 2020;40:37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41232-020-00146-3.

Joly BS, Siguret V, Veyradier A. Understanding pathophysiology of hemostasis disorders in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Intensive Care Med. 2020;1:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06088-1.

Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5.

Abou-Ismail MY, Diamond A, Kapoor S, Arafah Y, Nayak L. The hypercoagulable state in COVID-19: incidence, pathophysiology, and management. Thromb Res. 2020;194:101–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2020.06.029.

Radenkovic D, Chawla S, Pirro M, Sahebkar A, Banach M. Cholesterol in relation to COVID-19: should we care about it? J Clin Med. 2020;9:1909. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9061909.

Castiglione V, Chiriacò M, Emdin M, Taddei S, Vergaro G. Statin therapy in COVID-19 infection. Eur Hear J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa042.

Lee KCH, Sewa DW, Phua GC. Potential role of statins in COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96:615–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.115.

Fedson DS. Treating influenza with statins and other immunomodulatory agents. Antiviral Res. 2013;99:417–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.06.018.

Grudzinska FS, Dosanjh DP, Parekh D, Dancer RC, Patel J, Nightingale P, et al. Statin therapy in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Med (Northfield Il). 2017;17:403–7. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.17-5-403.

Cariou B, Goronflot T, Rimbert A, Boullu S, Le May C, Moulin P, et al. Routine use of statins and increased mortality related to COVID-19 in inpatients with type 2 diabetes: Results from the CORONADO study. Diabetes Metab. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2020.10.001.

Zhang XJ, Qin JJ, Cheng X, Shen L, Zhao YC, Yuan Y, et al. In-hospital use of statins is associated with a reduced risk of mortality among individuals with COVID-19. Cell Metab. 2020;32(176–187):e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2020.06.015.

Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. (2020) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses 2013. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 17 Aug 2020

Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region. Italy: Jama; 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5394.

Saeed O, Castagna F, Agalliu I, Xue X, Patel SR, Rochlani Y, et al. Statin use and in-hospital mortality in diabetics with COVID-19. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.018475.

Rodriguez-Nava G, Trelles-Garcia DP, Yanez-Bello MA, Chung CW, Trelles-Garcia VP, Friedman HJ. Atorvastatin associated with decreased hazard for death in COVID-19 patients admitted to an ICU: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24:429. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03154-4.

Lala A, Johnson KW, Januzzi JL, Russak AJ, Paranjpe I, Richter F, et al. Prevalence and impact of myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:533–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.007.

De Spiegeleer A, Bronselaer A, Teo JT, Byttebier G, De Tré G, Belmans L, et al. The effects of ARBs, ACEIs and statins on clinical outcomes of COVID-19 infection among nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.018.

Krishnan S, Patel K, Desai R, Sule A, Paik P, Miller A, et al. Clinical comorbidities, characteristics, and outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients in the State of Michigan with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. J Clin Anesth. 2020;67:110005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.110005.

Mallow PJ, Belk KW, Topmiller M, Hooker EA. Outcomes of hospitalized COVID-19 patients by risk factors: results from a united states hospital claims database. J Heal Econ Outcomes Res. 2020;7:165–75. https://doi.org/10.36469/jheor.2020.17331.

Rossi R, Talarico M, Coppi F, Boriani G. Protective role of statins in COVID 19 patients: importance of pharmacokinetic characteristics rather than intensity of action. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15:1573–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-020-02504-y.

Masana L, Correig E, Rodríguez-Borjabad C, Anoro E, Arroyo JA, Jericó C, et al. Effect of statin therapy on SARS-CoV-2 infection-related. Eur Hear J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa128.

Song SL, Hays SB, Panton CE, Mylona EK, Kalligeros M, Shehadeh F, et al. Statin use is associated with decreased risk of invasive mechanical ventilation in COVID-19 patients: a preliminary study. Pathogens. 2020;9:759. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9090759.

Daniels LB, Sitapati AM, Zhang J, Zou J, Bui QM, Ren J, et al. Relation of statin use prior to admission to severity and recovery among COVID-19 inpatients. Am J Cardiol. 2020;136:149–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.09.012.

Kow CS, Hasan SS. Meta-analysis of effect of statins in patients with COVID-19. Am J Cardiol. 2020;134:153–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.08.004.

Hariyanto TI, Kurniawan A. Statin therapy did not improve the in-hospital outcome of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:1613–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.08.023.

Bifulco M, Gazzerro P. Statins in coronavirus outbreak: It’s time for experimental and clinical studies. Pharmacol Res. 2020;156:104803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104803.

Vandermeer ML, Thomas AR, Kamimoto L, Reingold A, Gershman K, Meek J, et al. Association between use of statins and mortality among patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infections: a multistate study. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:13–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jir695.

Laidler MR, Thomas A, Baumbach J, Kirley PD, Meek J, Aragon D, et al. Statin treatment and mortality: propensity score-matched analyses of 2007–2008 and 2009–2010 laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2:ofv028. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofv028.

Fedson DS. Treating the host response to emerging virus diseases: lessons learned from sepsis, pneumonia, influenza and Ebola. Ann Transl Med. 2016. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2016.11.03.

Fedson DS, Opal SM, Rordam OM. Hiding in plain sight: an approach to treating patients with severe covid-19 infection. MBio. 2020;11:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00398-20.

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(271–280):e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052.

Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis MLC, Lely AT, Navis GJ, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203:631–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1570.

Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, Zhong N, Slutsky AS. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:586–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9.

Tikoo K, Patel G, Kumar S, Karpe PA, Sanghavi M, Malek V, et al. Tissue specific up regulation of ACE2 in rabbit model of atherosclerosis by atorvastatin: Role of epigenetic histone modifications. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;93:343–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2014.11.013.

Wösten-Van Asperen RM, Bos AP, Bem RA, Dierdorp BS, Dekker T, Van Goor H, et al. Imbalance between pulmonary angiotensin-converting enzyme and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activity in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:438–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182a55735.

Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, Averill DB, Brosnihan KB, Tallant EA, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation. 2005;111:2605–10. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510461.

Cohen JB, Hanff TC, William P, Sweitzer N, Rosado-santander NR, Medina C, et al. Continuation versus discontinuation of renin—angiotensin system inhibitors in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: a prospective, randomised, open-label trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;2:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30558-0.

Wang K, Chen W, Zhou Y-S, Lian J-Q, Zhang Z, Du P, et al. SARS-CoV-2 invades host cells via a novel route: CD147-spike protein. bioRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.14.988345.

Reiner Ž, Hatamipour M, Banach M, Pirro M, Al-Rasadi K, Jamialahmadi T, et al. Statins and the COVID-19 main protease: in silico evidence on direct interaction. Arch Med Sci. 2020;16:490–6. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2020.94655.

Huang I, Pranata R, Lim MA, Oehadian A, Alisjahbana B. C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, D-dimer, and ferritin in severe coronavirus disease-2019: a meta-analysis. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2020;14:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753466620937175.

Lim MA, Pranata R, Huang I, Yonas E, Soeroto AY, Supriyadi R. Multiorgan failure with emphasis on acute kidney injury and severity of COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Kidney Heal Dis. 2020;7:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2054358120938.

Koushki K, Shahbaz SK, Mashayekhi K, Sadeghi M, Zayeri ZD, Taba MY, et al. Anti-inflammatory action of statins in cardiovascular disease: the role of inflammasome and toll-like receptor pathways. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-020-08791-9.

Moutzouri E, Tellis CC, Rousouli K, Liberopoulos EN, Milionis HJ, Elisaf MS, et al. Effect of simvastatin or its combination with ezetimibe on Toll-like receptor expression and lipopolysaccharide—induced cytokine production in monocytes of hypercholesterolemic patients. Atherosclerosis. 2012;225:381–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.08.037.

Luo W, Yu H, Gou J, Li X, Sun Y, Li J, et al. (2020) Clinical pathology of critical patient with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19). Preprints 2020:1–18. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202002.0407/v4. Accessed 19 July 2020

Paranjpe I, Fuster V, Lala A, Russak A, Glicksberg BS, Levin MA, et al. Association of treatment dose anticoagulation with in-hospital survival among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.001.

Sahebkar A, Serban C, Ursoniu S, Mikhailidis DP, Undas A, Lip GYH, et al. The impact of statin therapy on plasma levels of von Willebrand factor antigen: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115:520–32. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH15-08-0620.

Sahebkar A, Kotani K, Serban C, Ursoniu S, Mikhailidis DP, Jones SR, et al. Statin therapy reduces plasma endothelin-1 concentrations: a meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241:433–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.05.022.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HP: conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, supervision. IH: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, validation, resources, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. AP: software, validation, data curation, formal analysis, visualization. NYK: writing—review and editing, supervision. TAS: writing—review and editing, supervision. EM: writing—review and editing, supervision. RW: writing—review and editing, supervision. NNMS: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Permana, H., Huang, I., Purwiga, A. et al. In-hospital use of statins is associated with a reduced risk of mortality in coronavirus-2019 (COVID-19): systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol. Rep 73, 769–780 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43440-021-00233-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43440-021-00233-3